|

Equine Gastric Ulcers: A Real Problem with a Natural Solution

By Dr. Richard Shakalis (co-founder and researcher for SBS Equine Products)

Gastric ulcers and are a major health concern for horses.

A gastroendoscopic study (Murray et al.) of all breeds of horses from one to twenty four years old showed more than 52 percent to have gastric ulcers. When only racehorses were tested, the

incidence of gastric ulcers was even greater.

A post mortem evaluation of thoroughbred horses in Hong Kong which consisted of both active

and retired racers found gastric ulceration in 66 percent of all the horses examined. When only active thoroughbred racers were considered, the incidence increased to over 80 percent.

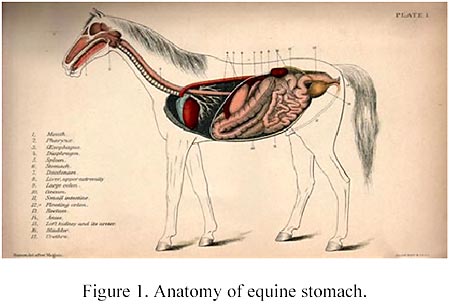

Another extensive series of tests by The Equine Gastric Ulcer Council independently confirmed these findings. They found gastric ulcers present in 80-90 percent of racehorses in training. These

ulcers developed in the fundic area of the stomach, the very starting point of the digestive process. (See Top Picture.)

Foals are also subject to ulcers and it is well known they can cause morbitity and mortality (Becht and Beyers). At birth, the equine gastric epithelium is thin and lowly keratinized (Murray and

Mahaffey). Foals can produce substantial stomach acid at an early age (Baker and Gerring, Sanchez et al). They observed gastric pH readings of 4 and less in two day old foals and readings

of pH 2 and lower in week old animals. Foals with gastric ulcers tend to exhibit intermittent nursing, poor appetite, colic, poor body condition, diarrhea, bruxism and ptylism (Jones). A severe ulcer

may result in foals rupturing their stomachs.

Why Horses Get Gastric Ulcers

Horses have evolved to eat many small meals per day, almost on a continual basis. Even though the

horse’s stomach is only 8 percent of digestive tract (eight quarts or two gallons), the emptying time

of the stomach can be a mere twelve minutes and the rate of passage through the small intestine one

foot per minute. The small volume of the stomach and the rapid passage of food to the small

intestine is the reason that horses can and are designed to eat almost continuously (Wright). Gastric pH can drop lower than 2 soon after a horse stops consuming food (Murray and Schusser) and the

stomach will continue to produce strong acid even if food is not present.

Concentrate feeding can inadvertently contribute to ulcer formation by its influence on increasing

serum gastric levels, lowering the horse’s roughage intake and reducing the amount of time spent eating (Campbell-Thompson and Merritt). Imposed feed deprivation, such as in colic management

cases, can result in erosion and ulceration of the gastric mucosa as well (Murray).

In the case of racehorses, they are often not fed immediately prior to training or racing. This could

result in a significant increase in stomach acidity. Also, horses can become excited during training

and racing, further lowering gastric pH. These influences contribute to gastric ulceration (Vatistas et

al.) Studies show that the greater the degree of training activity, the increasing severity of gastric

lesions (Murray et al., Equine Gastric Ulcer Council). Further, lesions were induced and maintained in thoroughbred horses during simulated training, using a diet of coastal Bermuda and concentrate

(Murray). Although Dr. N. J. Vatistas stopped short of recommending all racehorses in training

receive gastric ulcer treatment, he did indicate that “The truth may not be far from that” (Jones).

Other Risk Factors

The prevalence of gastric ulcers in horses competing in 3-day events has been observed to be 75 percent (Murray). Horses exercised at maximal intensity (gallop) have significantly greater number

and severity of gastric lesions than horses exercised at a trot (Murray). Jones also implicated the link between intensity of exercise and gastric ulceration. Illness is a risk factor for ulcer

development (Jones). Also, antagonism of prostaglandin synthesis through use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. aspirin, ibuprofen) is a well known cause of ulceration in foals and horses

(Traub et al., MacAllister et al.). Either long-term use at a normal dose or a single overdose can induce ulcers in horses (Smith). Adult horses with ulcers exhibit a combination of poor appetite,

dullness, attitude changes, decreased performance, poor body condition, rough hair coat, weight loss and colic (Jones).

Ulcer Formation Mechanism

Gastric ulceration in horses results from an imbalance between offensive factors, e.g. acid and pepsin, and defensive factors such as mucus, bicarbonate, prostaglandins, mucosal blood flow and

epithelial restitution (Geor and Papich). Most of these ulcers occur in the fundic portion of the stomach, which has a phospholipid rich, protective epithelial layer. Disruption of this barrier

(mucous, surface-active phospholipids) is initial to the destruction of the stomach’s surface epithelium. Because most domesticated horses do not feed constantly like nature designed them to,

excess acid can ulcerate this protective layer. (For a discussion of membranes see Russett). Unless the mucous lining is strong enough to withstand the powerful acids produced here, ulcers often

develop.

Management of Equine Gastric Ulcers

Various therapeutic protocols have been suggested for the control of equine gastric ulcers. These

include antacids, (think of products such Tums and Rolaids) and H2 acid blockers such as the pharmaceutical products Pepsid and Prilosec. These treatments will reduce acid in the fundic

portion of the stomach and will reduce the occurrence of ulcers, but there may be unintended negative consequences from these treatments. Stomach acid is an extremely important component

of the initial stage of the digestive process. If in this initial stage of digestion there is not adequate

acid present to break down food, it will pass into the small intestine only partially digested. The

nutrients won’t be in a form that can be absorbed in the small intestine and the horse will not be

adequately nourished. A carefully designed nutritional program may be inadvertently compromised. Shutting off stomach acid is not the answer.

There is a better way to protect the horse from and treat gastric ulcers. When the horse is given

lecithin as a nutritional supplement to his normal diet, the acid in the fundic portion of the stomach

immediately breaks it down into a mix of reactive phospholipids. The phospholipids in lecithin are both hydrophilic and hydrophobic and interact with the cell membranes of the mucosal epithelium to

strengthen the mucosa. Research has shown that lecithin not only treats the symptoms of equine ulcers, it cures the ulcers as well by making the stomach lining stronger at the cellular membrane level.

The beneficial effects of a diet supplemented with lecithin also enhances the rest of the digestive

tract as well. There has been much research to substantiate this. Lichtenberger et al. and Ghyczy et al. found that feeding rats exogenous mixed phospholipids prevented gastric irritation while

enhancing lipid permeability and therapeutic activity. They also found that soy phosphatidylcholine (a phospholipid found in lecithin) reduced stomach pain in people with gastric distress. They

concluded that orally administered lecithin was a natural way to protect the stomach from dangerous substances. Other researchers (Venner, Geor) also concluded lecithin was a cost

effective way to treat equine gastric ulcers and provide long term maintenance of affected horses. Another proposed protective mechanism is that phospholipids help with cell membrane turnover or

wound-resealing in the surface epithelium (McNeil and Ito). A hypothesis is that exogenous (i.e. dietary) phospholipids may promote a continuous wound resealing process, perhaps by providing

simple structural elements for the process (Kiviluoto et al.). Researchers at VPI (Holland et al.) confirmed the palatability and digestibility of soy lecithin and behavior in horses. They observed

horses fed lecithin had reduced levels of excitability and anxiety that was attributed to the healing of gastric ulcers.

What is Lecithin?

Lecithins are natural components of living organisms, both plants and animals. Commercial lecithin is made by processing soybeans and is a complex mixture of surface acting agents such as

phospholipids and contains nutrients including linoleic acid (omega 6) and linolenic acid (omega 3),

two essential fatty acids. The term lecithin is a general one and the actual composition of its active mixed phospholipids may vary between 50 and 97 percent, depending on the neutral lipid content.

When the term lecithin is used in this article it refers to a specific composition that has shown to be

effective in treating equine ulcers. This form of lecithin has a specific mix of phospholipids containing

a hydrophobic portion with an affinity for fats and oils, and hydrophillic portion with an affinity for

water. It strengthens the cell membranes of the digestive tract and can act as a short term physical barrier to acid in the fundic area of the stomach.

Summary

A well studied health condition in horses is gastric ulcers. The presence of these ulcers is associated with poor condition, irritability and poor performance. Treatment options such as

reducing stomach acid production is expensive and can disrupt the normal digestive process by not allowing the food to begin its initial breakdown as nature intended. A less expensive and more

effective treatment is to give horses a nutritional supplement of lecithin. It strengthens the epithelial lining of the stomach treating

and preventing gastric ulcers and allow for the proper absorption of nutrients in the small intestine. The fact that lecithin also contains omega 6 and omega 3 fatty acids is a nutritional bonus.

Lecithin not only treats the ulcers, it helps maintain the integrity of the plasma membranes of the skin, hair, coronary band

(promotes healthy hoof growth), and nerve tissues. Lecithin has proven a valuable natural supplement for to be horses to treat and prevent gastric ulcers. It also has shown to benefit other

animals as well as man when added to their diets. We are becoming increasingly aware of the quality and longevity of our lives and those of our companion animals and the important role that

nutrition plays. No longer do we consider the term adequate nutrition to be acceptable as we and our companion animals live longer, more vibrant lives. Adequate is just not good enough. Optimal

nutrition should become the new standard.

A well studied health condition in horses is gastric ulcers. The presence of these ulcers is associated with poor condition, irritability and poor performance. Treatment options such as

reducing stomach acid production is expensive and can disrupt the normal digestive process by not allowing the food to begin its initial breakdown as nature intended. A less expensive and more

effective treatment is to give horses a nutritional supplement of lecithin. It strengthens the epithelial lining of the stomach treating

and preventing gastric ulcers and allow for the proper absorption of nutrients in the small intestine. The fact that lecithin also contains omega 6 and omega 3 fatty acids is a nutritional bonus.

Lecithin not only treats the ulcers, it helps maintain the integrity of the plasma membranes of the skin, hair, coronary band

(promotes healthy hoof growth), and nerve tissues. Lecithin has proven a valuable natural supplement for to be horses to treat and prevent gastric ulcers. It also has shown to benefit other

animals as well as man when added to their diets. We are becoming increasingly aware of the quality and longevity of our lives and those of our companion animals and the important role that

nutrition plays. No longer do we consider the term adequate nutrition to be acceptable as we and our companion animals live longer, more vibrant lives. Adequate is just not good enough. Optimal

nutrition should become the new standard.

Special thanks to the contributions of Dr. Craig Russett, Ph.D in Animal Nutrition.

Contact: Our Friendly Staff

3888 Mannix Dr., Unit 303

Naples, Florida 34114

Phone: 239-354-3361

Email: info@sbsequine.com

Website: www.sbsequine.com/startinggate.html

References

Acland, H.M.; D.E. Gunson and D.M. Gillette (1983). Ulcerative duodenitis in foals. Vet. Path 20:653-661.

Baker, S.J. and E.L. Gerring (1993). Gastric pH monitoring in healthy, suckling pony foals. Am. J. Vet. Res. 54:959-964.

Becht,J.L. and T.D. Byars (1986). Gastroduodenal ulcers in foals. Equine Vet. J. 18:307-313.

Campell-Thompson, M.L. and A.M. Merritt (1990). Basal and pentagastrin stimulated gastric secretion in

young horses. Am. J. Physiol. 259:R1259- R1266.

Equine Gastric Ulcer Council (1999). Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of equine gastric

ulcer syndrome(EGUS). Eqine Vet. Educ. 11(5):262-272.

Geor.R.j. and Papich (1990). Medical therapy for gastrointestinal ulceration in foals. Comp. Cont. Edu. Pract. Vet. 12:403-412.

Ghyczy,M., E. Hoff; J. Garzib (1996). Gastric mucosa protection by phosphatidylcholine (PC) Presented at: The 7th International Congress on Phospholipids, Brussels, Belgium.

Jones, W.E. (1999). Equine gastric ulcer syndrome. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 19:296-306.

Kiviluto, T.; H. Paimela, H. Mustonen and Kivilassko (1991). Exogenous surface active phosphpolipid

protects nectrus gastric mucosa agaist luminal acid and barrier breaking agents. Gastroenterology 100:38-46.

Lichtenberger, L.M.; Z. Wang, J>J> Romero, C ulloa, J.C. Perez, M.N. Giraud and J.C. Barreto (1995).

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) associate with zwitterionic phospholipids: insight into the mechanism and reversal of NSAID-induced gastro intestinal injury. Nature Med. 1:154-158.

Mcneil, P. ande S. Ito (1989). Gastrointestinal cell plasma membrane wounding and sealing in vivo. Gastroenterology 96:1238-1248.

Murray, M.J.; C.M. Murray, H.J. Sweeney, J. Weld, N.J. Digby Wingfield and S.J Stoneham (1996). The prevalence of gastric ulcers in foals in Ireland and England: An edoscopic survey. Equine Vet. J. 28

(5):368-374.

Russett, J.C. (1997). Lecithin applications in animal feeds. Specialty Products Research Notes. LEC-D-56.

Smith, C.A. (1991). Could your horse have an ulcer? The Morgan Horse. Sept. pp 114-116.

Traub, J.L.; A.M. Gallina, B.D. Grant, S.M. Reed, P.R. Gavin and L.M. Paulsen (1983). Phenylututazone

toxicosis in the foal. Am. J. Vet. Res. 44:1410-1418.

Vatitstas, N.J.; Snyder, G. Carlson, B. Johnson, R.M. Arthur, Thurmond, and K.C.K. Lloyd (1994).

Epidemiological study of gastric ulceration in the Thoroughbred racehorse: 202 horses 1992-1993. 40th AAEP Convention Proceedings. pp 125-126.

Venner, M.; S. Lauffs and E. Deegen (1999). Treatment of gastric ulcers in horses with pectin-lecithin complex. Eqine Vet. J. Suppl. 29:91-96.

Wright, B. (1999). Equine digestive tract structure and function. Ontario Ministry of Agriculture.

|